When we think about innovation in the circular economy, we often imagine big research teams, large institutions, and corporate labs. But sometimes, the biggest ideas come from the smallest players.

One of the partners in the FlashPhos project is MITechnology, a one-person enterprise founded and led by Alfred Edlinger – a chemist, inventor, and process developer based in Austria. His company focuses on turning complex waste materials into usable resources, with projects centered on circular economy, CO₂ minimization, and thermochemical upcycling.

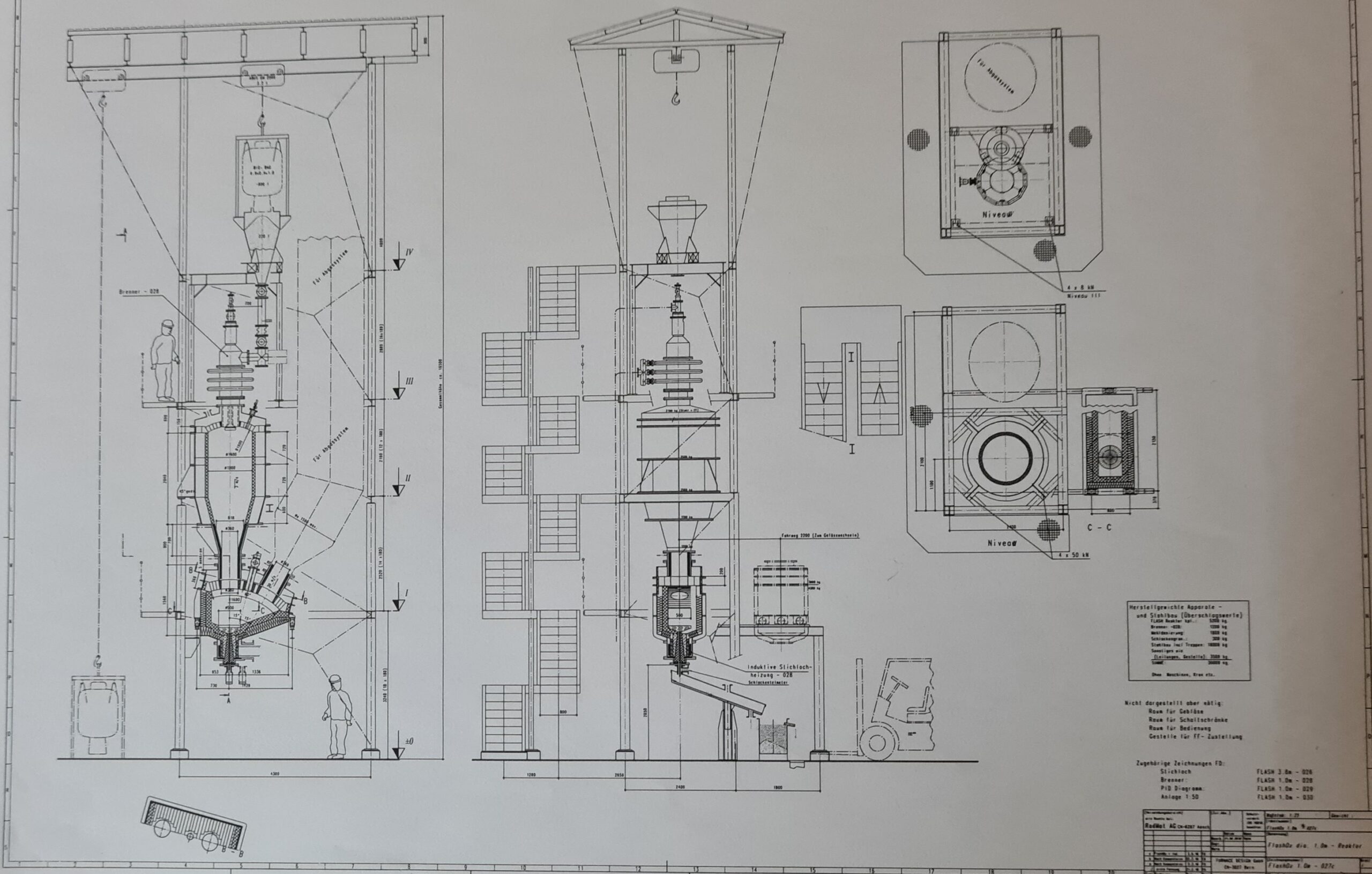

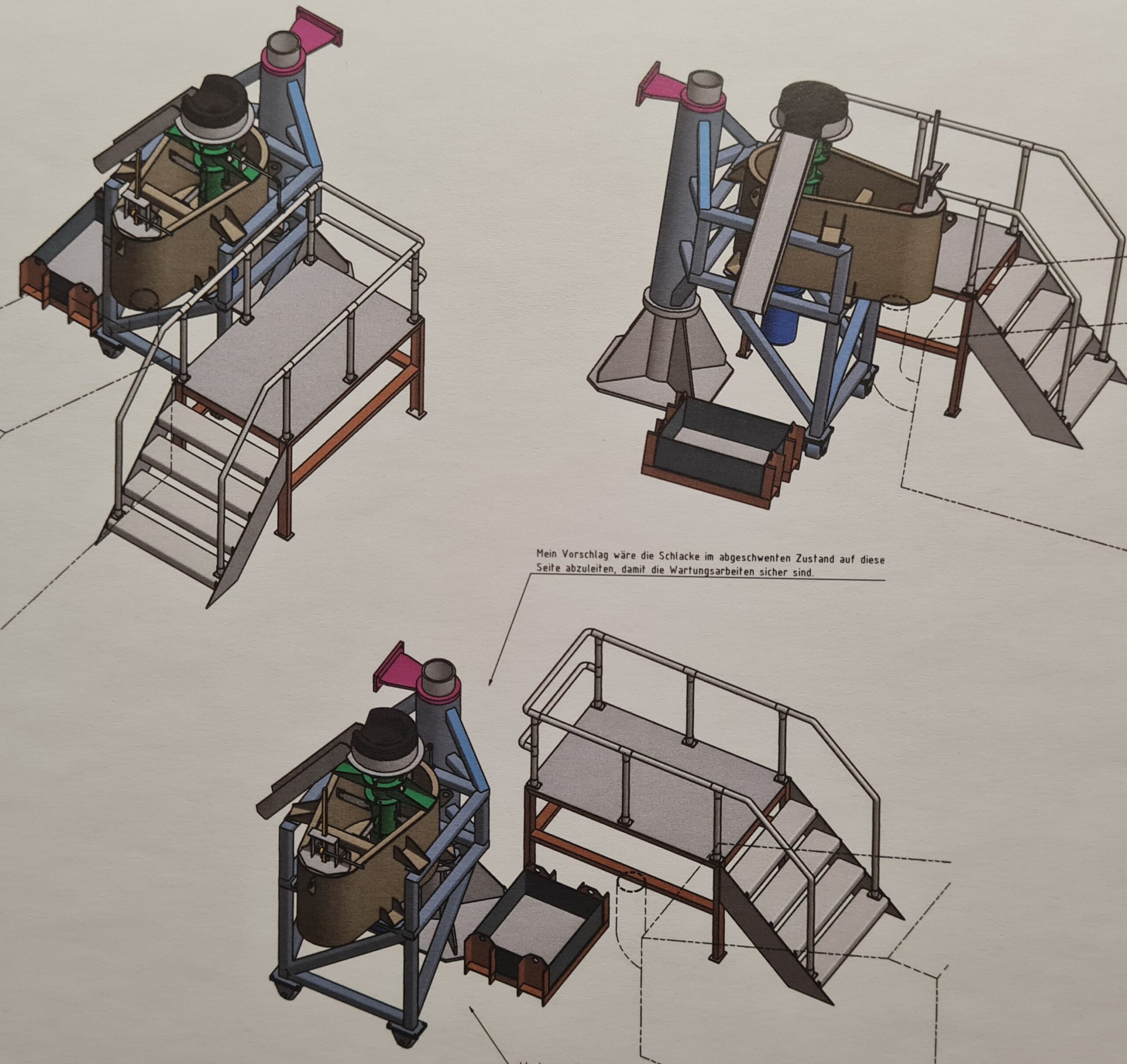

Alfred is no stranger to bold ideas: from pioneering the FlashPhos process to developing innovative granulation methods for mineral melts, his inventions are paving the way for sustainable, industrial-scale applications. And despite its small size, MITechnology plays a key role in helping the EU move toward resource independence and lower emissions.

We sat down with Alfred to talk about what it means to invent, how ideas become patents and products, and why innovation doesn’t have to come from big labs to make a global impact.

Interview

Part 1: The Mindset of an Inventor

1. Alfred, you’re an inventor. What part of inventing excites you the most?

Actually, I am registered in the European Patent Office database Espacenet as the inventor of 688 patents. My goal is to contribute to a better world by transforming organic and inorganic wastes into valuable raw materials – such as cement, hydrogen, and phosphorus – while minimizing CO₂ emissions and energy demand under economically viable conditions.

2. Indeed, many of your processes focus on waste transformation and circularity. What motivates you to work on these topics?

My motivation comes from a deep interest in chemistry and thermodynamics. I’m eager to learn more by conducting research in these fields – and I want to contribute to environmental protection.

3. What’s the difference between an invention and an innovation in your view?

As often said: invention is 5%, and innovation is 95% of the total effort. However, achieving innovation without invention can be difficult. In fact, new inventions often emerge during the innovation process – as seen in the FlashPhos project.

Part 2: From Idea to Impact

4. What sparks a new idea for you? Do inventions start with a technical challenge, a material, or something else entirely?

I observe current ecological and economic problems in our society and compare them with my intellectual capabilities in chemistry, thermodynamics, and process engineering. From there, I begin shaping possible concepts.

5. How do you turn a creative idea into something that works in the real world?

I begin with theoretical considerations and calculations to evaluate new ideas, before I start working in my small laboratory to verify the possible concepts. Then I usually apply for financial support from the Austrian Research Foundation (FFG Vienna) – for example, through the PatentScheck for patenting and InnoScheck for scientific evaluation. This evaluation is carried out in collaboration with universities. Patents and scientific validation then form the basis for larger projects, such as EU-funded initiatives. Awards like the Scientific Award or Austrian State Prizes are also helpful for visibility and support.

6. What role do patents play in your work? Do they protect your ideas, enable collaboration – or both?

Definitely both. My main source of income comes from licensing my patents.

7. You work closely with industry partners. How important is it for inventors to stay connected to real-world industrial problems?

This is one of my main priorities. My ideas should not remain purely academic. Although I’m not a strong project coordinator myself, I’m committed to supporting realistic, practical projects that are environmentally relevant.

Part 3: Lessons and Outlook

8. What is one invention you’re particularly proud of – and what challenge did it solve?

One of my most exciting current projects is ChemQuench, which transforms organic waste into hydrogen – and is already at the industrial stage. Of course, FlashPhos is also very important, as it addresses future challenges in the circular economy (Green Deal). I’m also working on Loop2Phos together with the University of Stuttgart. It has similar goals to FlashPhos but with CO₂-negative performance, as it uses the carbon content in sewage sludge instead of coke, which also leads to significant energy savings.

9. MITechnology is a one-person company – and yet you’re involved in major EU projects. What are the advantages of being small and independent?

A high degree of flexibility and freedom to work within EU projects. This also makes innovative work possible – and often leads to new patents.

10. What advice would you give to other inventors or small enterprises who want to make a difference in the circular economy?

Invent, innovate, cooperate!

11. Looking ahead: what unsolved problem in industry would you love to tackle next?

I’m looking at new ecological and economic solutions for energy savings and CO₂-free industrial and municipal processes.

Some Impressions

Click through the photos to see what inventing looks like in real life – from lab to prototype:

Why This Matters

In the race to reduce emissions, close material loops, and build sustainable industries, we need fresh thinking. Inventors like Alfred Edlinger remind us that innovation doesn’t always require a big budget – but it does require curiosity, persistence, and a deep understanding of real-world problems.

At FlashPhos, we are proud to work with partners like MITechnology, who bring agility and creativity to the table. Their role is crucial in making waste valorization technologies not just scientifically sound, but industrially viable.